エッセイ エッセイ一覧

[エッセイ11:ひょんなことからNo.5]Are you a Roman Catholic Priest or Fieldworking Anthropologist? :Some Hidden Memories about the Kakure Kirishitan Survivors in Nagasaki Settings(MUNSI, Roger Vanzila)

2019年05月03日

[A sudden twist of fate 05]

Are you a Roman Catholic Priest or Fieldworking Anthropologist?

Some Hidden Memories about the Kakure Kirishitan Survivors in Nagasaki Settings

ムンシ・ロジェ・ヴァンジラ

MUNSI, Roger Vanzila

人類学研究所・第二種研究所員

The present-day remnants of Kakure Kirishitan (Hidden Christian) communities in Nagasaki Prefecture are descendants of the early Japanese Christian converts and the underground Christians/Catholics who survived the severe persecution by the Japanese authorities, especially between 1614 and 1873. The exact reasons for this are varied. The most likely explanation is that their persecution had more to do with the conversion of warlords and vassals who ended up on the losing side, than with anything doctrinal. Left without priests, the early Japanese Crypto-Christians developed their own rituals, liturgies, symbols, and a few texts, adapting them from remnants of 16th century Portuguese Catholicism and often camouflaging them in forms borrowed from the surrounding Buddhism and Shinto. Although the hidden Christian communities have been tolerated by the Japanese authorities for almost 150 years now, remnants of them have continued their separate and private life as independent, Christian communities. Evidently, religiously active members are significantly grappling with their relationship to a community that is at once both a source of psycho-religious and spiritual comfort and concern. Today these faith-based communities (with 1500 to 2000 adherents as of July 2018) nevertheless constitute a tiny, marginalized minority of the local populace, and their survival is in question.

I write this essay out of particular personal concern and interest, for some of my hidden memories in Nagasaki settings are quite different from the superficial accounts that many readers frequently read in this restricted field of Kakure Kirishitan studies. In fact, I have been holding these field notes back for some time and only submit them now as a contribution to this homepage corner: "A sudden twist of fate" of the Nanzan Anthropological Institute. For the sake of space, however, I cannot provide readers with all the details. Only one part of my records are presented and simplified in the following lines.

|

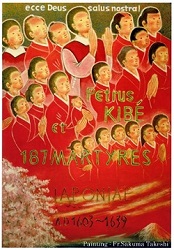

On 24 November 2008, Peter Kibe and 187 Japanese Christian martyrs of the seventeenth century were beatified (or proclaimed blessed) in Nagasaki city. Their beatification was reportedly the first ever celebrated in Japan, marking the pivotal moment in the history of the local Catholic Church literature. In the Roman Catholic Church, the term "beatification" (from Latin beatus, "blessed" and facere, "to make") typically denotes an "administrative act" by which the pope allows a candidate for sainthood to be venerated publicly in places closely associated with his or her life and ministry; the place may be as small as one city, although usually it is the diocese where the person lived or died. After beatification, the venerable person is then called "Blessed." Peter Kibe and 187 Japanese Christian martyrs were therefore recognized by the Catholic Church in their capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their names. Interestingly enough, however, they included noblemen, priests--four of them--and one religious. But most of them were ordinary Christians: farmers, women, young people under the age of twenty, even small children, and entire families. All of them were killed for refusing to renounce the Christian faith. Even though two of these Japanese martyrs, Nakaura Julian and Kinnoba Jihyōe, were from Sotome-Kurosaki and hence connected to the Kakure Kirishitan communities, the local Catholic Church did not send a single invitation to the Kakure Kirishitan practitioners. Of course they could attend the solemn ceremony without any (formal) invitation. But the attitude of the local Catholic Church officials was keenly disappointing to them. In a similar way, at the beginning of the discernment, they somehow related it to the deeply entrenched tendency of some local Catholic Church officials to neglect the virtue of the continued existence of their faith-based communities in today's Nagasaki settings. That was perhaps the very reason why Kakure Kirishitan believers in Kurosaki purposely decided to schedule a wedding ceremony on the same day and at the same time of the beatification.

|

|

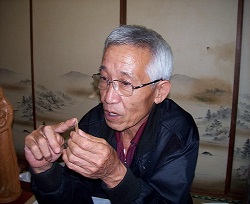

On account of my long period of social interaction with them, Murakami Shigenori--the community formal leader or Chōkata帳方of Kakure Kirishitan survivors in Shimo-Kurosaki--unexpectedly invited me (a Roman Catholic Priest) to officiate at the wedding ceremony of his eldest daughter, Murakami Mika, to a Pure Land Buddhist, Nambu Tetsuaki on that particular day. This was perhaps because the Kakure Kirishitan leader wanted, in his own way, to participate in orthodox Catholicism; perhaps because he honestly questioned the authority traditionally placed in him to perform the sacrament. Consequently, I had to decide to either attend the solemn ceremony of Beatification in Nagasaki city or take the opportunity to preside over the unprecedented wedding ceremony in the present-day Shimo-Kurosaki district (formerly Sotome district), the setting of Shusaku Endo's acclaimed Novel Silence--which deftly draws from the oral history of the local Kirishitan communities pertaining to the time of suppression of the local Catholic Church. In the end, I opted for the second idea, which I thought was also one of the benefits of my ethnographic fieldwork experience (I had sound academic reasons, and not just nebulous spiritual and pastoral ones, for taking part in such a decidedly religious setting). This was, to the best of my knowledge, the first event of this genre not only in the region, but also in the history of both the local Catholic Church and of the Kakure Kirishitan Society. How was then this rare, usually brief, wedding ceremony held?

The wedding staging of the day required that Kakure Kirishitan practitioners come together at the Hostel Hall, and the Catholic Church pattern of the marriage between a Christian and non-Christian was part of the ritual procedure. As the Hall bell was rung to bring the attention of the audience, Kakure Kirishitan families were quite surprised to see a Catholic priest appearing in the Wedding Hall, wearing a white alb and a stole above his chasuble (a Christian liturgical vestment used in the Eastern and Western Churches) both designed with the image of a leopard (a totem animal of the Sakata people in the hinterland of the Democratic Republic of Cong (formerly Zaïre). Then I moved on to preside over the 40-minutes wedding ceremony between Nambu and Mika. Thereafter, however, I surprisingly learned that the presumed "non-Christian" was already baptized by the formal leader of The Kakure Kirishitan community in Shimo-Kurosaki before the actual wedding ceremony. From the Catholic Church's point of view, their marriage becomes canonically sacramental, once baptism took place. There were about 100 participants, with Kakure Kirishitan believers forming the majority.

|

|

Intriguingly in this specific religious setting, these religiously committed Kakure Kirishitan families, who significantly considered the past as the ultimate source of their religious culture and identity, vehemently acted through the spiritual intercession of their deceased predecessors or righteous ancestors in faith with whom their share ethnicity, historical and Christian/catholic roots--while allowing permutations of form and content. It transpired that many of them came from different areas, including Oita, Fukouka, Sasebo, and Nagasaki, a factor that demonstrates the extent to which it will be worthwhile to observe for a couple of decades the continuation of Kakure Kirishitan faith focused on individuals rather than "focused on community. As usual, the wedding reached the climax when the bride and groom took the vows and exchanged rings. The ceremony proceeds in a solemn and touching atmosphere with families, visitors, and a great number of Kakure Kirishitan participants moving in one direction.

During the recitation of the Lord's Prayer [Pater Noster] - in distorted Latin mingled with Portuguese and Japanese words - one could, through the melodic rhythm and bodily gestures of participants, sense the strong presence of Kakure Kirishitan practitioners in the hall. On the surface each participant contributed his or her own words, emotions, and voice, but all fused together into a new and splendid whole. The rhythmic melody thus contained whole prayer sequences, allowing the interpenetration of secret dimensions, geographically and religiously remote entities of Kakure Kirishitan individuals and communities. Although physically remote from each other, they were momentarily reunited through what could be labeled an "acousmatic" vocal link. This is telling because what I experienced was essentially, as the Greek term άκουσμα (a-cousma) denotes, a sound which can be heard while its origin remained unknown to all participants. Such a collective prayer sound also acted as a dramatic driving force, melding various episodes or "acts" or "gestures', and allowing the action to unfold in a specific religious setting. In another sequence of the Orasho, the Kakure Kirishitan practitioners' vocal performance sounded like corporate religious minorities who struggle to achieve transition while retaining the persistence of the past, sustaining a kind of dialogue between the past and the present. On the other hand, a set of Catholic prayers I used during the ceremony helped them keep their spirits up (as they have been, unlike their predecessors, confronted with a diverse set of contextual, socio-cultural, and ethical issues and settings). True, after spending time to look elsewhere for a brief general introduction to the social life of the Kakure Kirishitan families, I then proceeded to the facets of this specific wedding ceremony for a closer look at the details.

|

|

The overall inescapable atmosphere of the wedding ceremony created a liminal context in which participants find themselves in a sacred time as they observed spouses, Nambu and Mika going through their specific rite of passage. These processes of the wedding ceremony thus shed new light on such themes as the porosity of borders between the real and the fantasized world, between past and present, between here and elsewhere, as well as the representation of invisible or so to say "aural and sacred spaces", without giving in to the customary distinction between their most acclaimed productions. Peculiarly enough though, the recurring presence of those liminal spaces is evoked in purely visual terms when it comes to their earlier collaborations. Suffice it to say that the occasion and workings of this specific wedding ceremony somehow contextualized the Orasho sequences through which Kakure Kirishitan individuals integrally became involved into a liminal setting with their tightly-knit members of communities and families, subsequent popular interest in religious objects and ideals, cultural ethos and social aspects. This overwhelming religious experience was followed by a party which not only brought participants together around a communal meal but also enlightened them with the inspiring speech made by Mika who described the contours of her life and the reminiscences of her grandfather, Murakami Shigeru, the former and prominent leader of Kakure Kirishitan survivors in Shimo-Kurosaki.

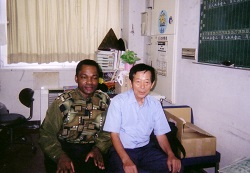

My social interaction of the present-day remnants of Kakure Kirishitan communities first took shape during my ethnographic fieldwork (2002-2007) in Sotome 外海町 (present-day Kurosaki黒崎町) and Ikitsuki生月町districts (Nagasaki prefecture) for my doctoral dissertation at Kanagawa University. The basic purpose of the project was to offer a contribution to the analysis of the most essential religious practices and related social aspects of Japan's Kakure Kirishitan survivors from an anthropological perspective. It is worth mentioning that a Japanese language program at Nanzan University, followed by pastoral work at Nishimachi Catholic Parish (Nagasaki), brought experiences and interests that proved compelling. At the beginning, some of my sample subjects were glad to see me in their midst, while others gave me a strange look and asked me what I had been up to and was really searching for in their social world. In such a new and unfamiliar setting, I had no idea of the expectations they had from me. I remember that I would do anything and everything I could to get the reassurance I wanted in this initial relationship. But there was a highly significant part of this first encounter. On the very first day of my pilot fieldwork I had to answer a particularly intriguing question that pinned my identity to a job instead of pinning a job to my bigger, evolving identity: "Are you a Roman Catholic Priest or Fieldworking Anthropologist?" Of course, at first glance, such a question seemed puzzling. But along the lines of social interaction with my sample subjects in their specific social world, it became telling. The highlight of the scenario, however, was not what I would immediately say--it was what the research participants thought of me and shared among themselves. Perhaps my informants aimed for a question that would invite me to tell stories, rather than giving bland, one-word answers. How could it be otherwise? Eventually, it was the first time that these seemingly integrated minority religious naturally interacted with a Congolese researcher whose background, ability, ingenuity, and drive appeared to them closely similar to those of a fervent Catholic and fieldworking anthropologist. Whatever one thinks about this, this single question cut right through to the core and ensured that I was making real conversation. My first experience of ethnographic fieldwork in Japan thus pushed me to think more critically about the purposes and challenges of doing participant observation in a setting that was almost completely unfamiliar to me.

However, in response to the question--"Are you a Roman Catholic Priest or Fieldworking Anthropologist?"--I decided at first to hide or conceal my proper identity as a Roman Catholic priest of the Society of the Divine Word from the Congo-Kinshasa. This attitude actually stemmed from the advice I received from my supervisor and senior researchers. At the very beginning I introduced myself simply as a Congolese researcher who was pursuing his doctorate studies at Kanagawa University. Because it sounded at that time that if I revealed that I am a Roman Catholic Priest, I would build a kind of "research wall" between the Kakure Kirishitan informants and myself. It was believed at that time that such a "research wall" would definitively hinder my relationship with my research participants as they might naturally suspect me to be a qualified spy from the local Catholic Church. Moreover, one could justifiably be concerned that revealing myself fully to these religious minorities would only encourage religious suspicions or, perhaps worse, diminish the religious commitment of those Kakure Kirishitan practitioners who were comfortable and keen to provide me with the necessary information for my research project. In terms of the latter, I have often bemoaned the fact that particularly within the Kakure Kirishitan communities there are many stakes involved in conducting in-depth interviews and conversations as the sample subjects often do not answer the questions fully. One needed to repeat the same questions several times and in different settings to expect accurate and detailed answers. Even today, of course, investigating into Kakure Kirishitan society is not without its challenges. So it was not entirely surprising that I would eventually try to hide myself for almost one year lest I do not achieve the aims of my fieldwork. I was painfully conscious of the deficiency involved in my concealing my identity, and had diligently tried to remedy it; but I could not escape the consequences of my initial lack of openness for the sake of research. Side by side with this we may place the following concern: "Such circumstances had often caused great sensation and engendered the fear that behind them was a plot aimed at compromising the present-day Kakure Kirishitan survivors".

In 2004, barely a year after my pilot study (2002-2003), I had the opportunity to revisit my field site for an intensive investigation of the Kakure Kirishitan practitioners. My research focused on the question of the past, present and future survival of the religion. To that end, my anthropological methodology required that I take the role of a participant observer who, in this case, had first to win the trust of the community formal leaders, particularly because of the secrecy of many aspects of the religion. But my interactions were also motivated by personal, more missionary interests: to learn what might be of benefit to my own religion (Catholicism), and to accommodate the wishes of some Kakure Kirishitan believers to participate in present-day Roman Catholicism. I was fortunate to have received from them some direct material and unpublished spiritual writings which contained a trove of evidence on Kakure Kirishitan survivors in the Meiji and Showa periods, with special attention paid to San Jiwan Sama (distorted Portuguese for St. John), with some regional "esoteric" or marginal currents and healing accounts sprinkled in for good measure. San Jiwan was reportedly a Portuguese missionary who took care of the Kakure Kirishitan survivors in the present-day Kurosaki (formerly Sotome) during the period of persecution. Despite some fine legendary tales that serve to define the saint's identity and his marvelous deeds in the region, including his supernatural qualities according to some believers, little is known about him. But this fact, according to Kakure Kirishitan informants, does not seem to really matter, for their long-standing religious sentiment towards San Jiwan depends on oral accounts of his deeds, transmitted over generations.

However, the question I asked myself was whether such a thing could enter the circle of Catholics who were friends of some of my Kakure Kirishitan informants. While I pondered this an incident occurred on 3 November 2004 during the 5th San Jiwan Karematsu Shrine festival. A devout Catholic woman from Nishimachi Catholic Church (Nagasaki) saw me in the crowd. She approached me, calling me loudly, "Roger Shimpu sama, hisashiburi desune," meaning "Father Roger, it's been a long time..." while I was just seating near one Kakure Kirishitan leader. It sounded risky and I was quite worried, thinking that everything related to my fieldwork would end up negatively on that day. Thankfully, the Kakure Kirishitan leader did not follow the whole scenario around me, as he was involved in a formal conversation with some local officials and journalists.

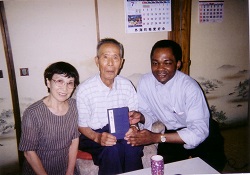

A year later, as I was completing my doctorate dissertation, I thought that it would better to go back to the field-site and reveal my identity, or so to say, complete the rest of my self-presentation. This was partly because I felt guilty and was worried that I had not introduced myself properly, although I received many things from my research participants. However, I did not know what I should exactly do to compensate for this. When I returned to the field-site, I was fortunate to receive support from Motoyama Shinobu, a Catholic woman from Urakami Catholic Church. As my Nagasaki "mother," she was heartily involved in the process. Thereafter I brought my souvenir/gift (おみやげOmiyage). While bowing in front of the Kakure Kirishitan leader, I apologized. By a proper lifting of the face, I then revealed by full identity. As expected, the coming out of the whole process was successful. Of my behavior one of the Kakure Kirishitan practitioners later said: "Through your behavior and the presence of your assistants, we just guessed that you were somehow related to the Catholic Church in Nagasaki, but we could not exactly confirm it without much information". Little did I know at the time that I was somehow treating my 'wounded soul" with core elements of authentic confession, a turning point which would become a cornerstone in my ongoing Catholic missionary life, anthropological research project, and academic profession or career. And in the end I appeared in my real identity as a Catholic priest and fieldworking anthropologist after my confession.

|

Indeed, there was an essential difference when I fully introduced myself. Feeling free and whole, my soul restored, I could return to Tokyo, where I furthered my academic reading and anthropological research project until I moved to Nagoya in 2008. The whole process effectively created a kind of tight, almost amical bond between the research participants and myself. Since then I smoothly pursued my studies into Kakure Kirishitan religion as a result of this experience, and I considered it my duty to communicate the message of this kind of Japanized Catholicism to the world. While conducting research on these religious minorities I found intriguing data that had not been previously reported in published ethnographic sources.

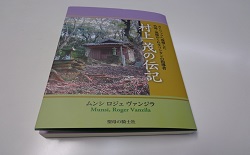

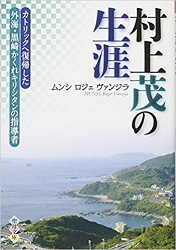

In 2012, barely eight years later, I published--through the lens of 'families' in Kakure Kirishitan society--a field study based book on The Biography of Murakami Shigeru: A Kakure Kirishitan Leader from Sotome-Kurosaki who converted to Catholicism. Yet, the word 'Biography' should not mislead any prospective reader, since the book, which received an Academic Award from the Japan's Association of Catholic Universities in June 2013, contains a profound richness of knowledge which could also satisfy an expert of the restricted field of Kakure Kirishitan studies. The same year I wrote an long article on the "San Jiwan Karematsu Shrine and Festival: Looking at the religiosity of the local Community". Two years later, at the beginning of Book II entitled The Life history of Murakami Shigeru: A Kakure Kirishitan Leader from Sotome-Kurosaki who converted to Catholicism, I further investigated the subject and felt immediately attracted to the present-day remnants of Kakure Kirishitan communities.

|

|

As my anthropological research deepened, it seems that the ties between Kakure Kirishitan communities and the local populace continued to get stronger. Then followed my field-based works whose contours and very existence are deeply accepted in scholarship, with encouraging appreciation and comments. The material of my ongoing anthropological project is thus a substantial collection of in-depth interviews (as contextualized conversations) with the present-day Kakure Kirishitan practitioners and the surrounding local community. My friendly relationship with them still continues today, inviting a level of perception and experience that can evoke deep respect and empathy. It is not surprising that I often get souvenirs from them and revisit twice a year my field-sites. Since then, there has been an air of excitement and discovery about my anthropological work. It is certain, however, that the social world of Kakure Kirishitan practitioners I have been studying seemed newly opened, and its paths were still uncharted. My field research endeavors also immersed me in socio-religious issues and historical events of the local community in the second half of the Heisei period which are, except tangentially, not reflected here. Apart from my field research experience, I have been in other settings asked if I was a fieldworking anthropologist or a Roman Catholic priest. Crucially, I was, in some instances, even asked to make a choice between the two positions. But I cannot opt for one position.

|

As things stand today, both positions instead seem relevant to my career. I still have a deep-felt need to carry out much research in this restricted field of Kakure Kirishitan studies only in the tranquility from my embedded position as both a fieldworking anthropologist and Roman Catholic priest. In particular, the study of the present-day remnants of Kakure Kirishitan communities is not usually common from a Catholic standpoint. Considering the contours of these seemingly integrated religious minorities in Nagasaki settings today, it is fair to say that I can take advantage of both positions in the field. Indeed I have over the past decades regarded my own participatory interactions with members of the Kakure Kirishitan communities as a kind of interreligious dialogue. But clearly I am not referring to verbal discussion about teachings. Instead my research focused on participation in practices, including some that did involve the use, if not the interpretation, of texts and patterns against the backdrop of the positive significant intersection of identities and ritual resources. Over the course of my 15-year social interaction with Kakure Kirishitan survivors, I had many experiences that allowed me to understand their faith-based communities and to see the many facets of religious beliefs and practices. Looking back I can fairly assert that I did obtain a great deal of my professional preparation and experience through the subsequent fieldwork research in Nagasaki settings.

More recently, I have been focusing on Kirishitan Shrines and Festivals, a theme that has sparked a renewal of academic interest for overarching motifs that had previously received scant attention. Suffice it to say that I had so far undertaken the writing of my anthropological work because I felt a genuine interest in his subject. It is therefore encouraging to see that the remnants of Kakure Kirishitan communities have recently been intriguing scholars and observers who tend to more carefully revisit and examine their faith-based community patterns, identities and ritual resources, psycho-religious and spiritual constructs against the backdrop of the UNESCO's recognition (July 2018) of the early Japanese Crypto-Christians' twelve historical sites as parts of the World Cultural Heritage. This intriguing facet of the subject also remains a work in progress.

|

|

(All photos courtesy of the author)